Mirror Left–Right Reversal Depends on Configuration — Only in Side Profiles

Contents

- 1 Chapter 1. The Standard View of Mirror Reversal

- 2 Chapter 2. Where the Standard Explanation Works—and Where It Breaks

- 3 Chapter 3. The Aim and Perspective of This Article

- 4 Chapter 4. The Key Insight: Observer–Mirror Configuration

- 5 Chapter 5. Why Six Configurations Are Sufficient

- 6 Chapter 6. The Six Fundamental Configurations Explained

- 6.1 Configuration ①: Frontal Orientation (Observer Facing the Mirror)

- 6.2 Configuration ②: Back Orientation (Observer's Back Toward the Mirror)

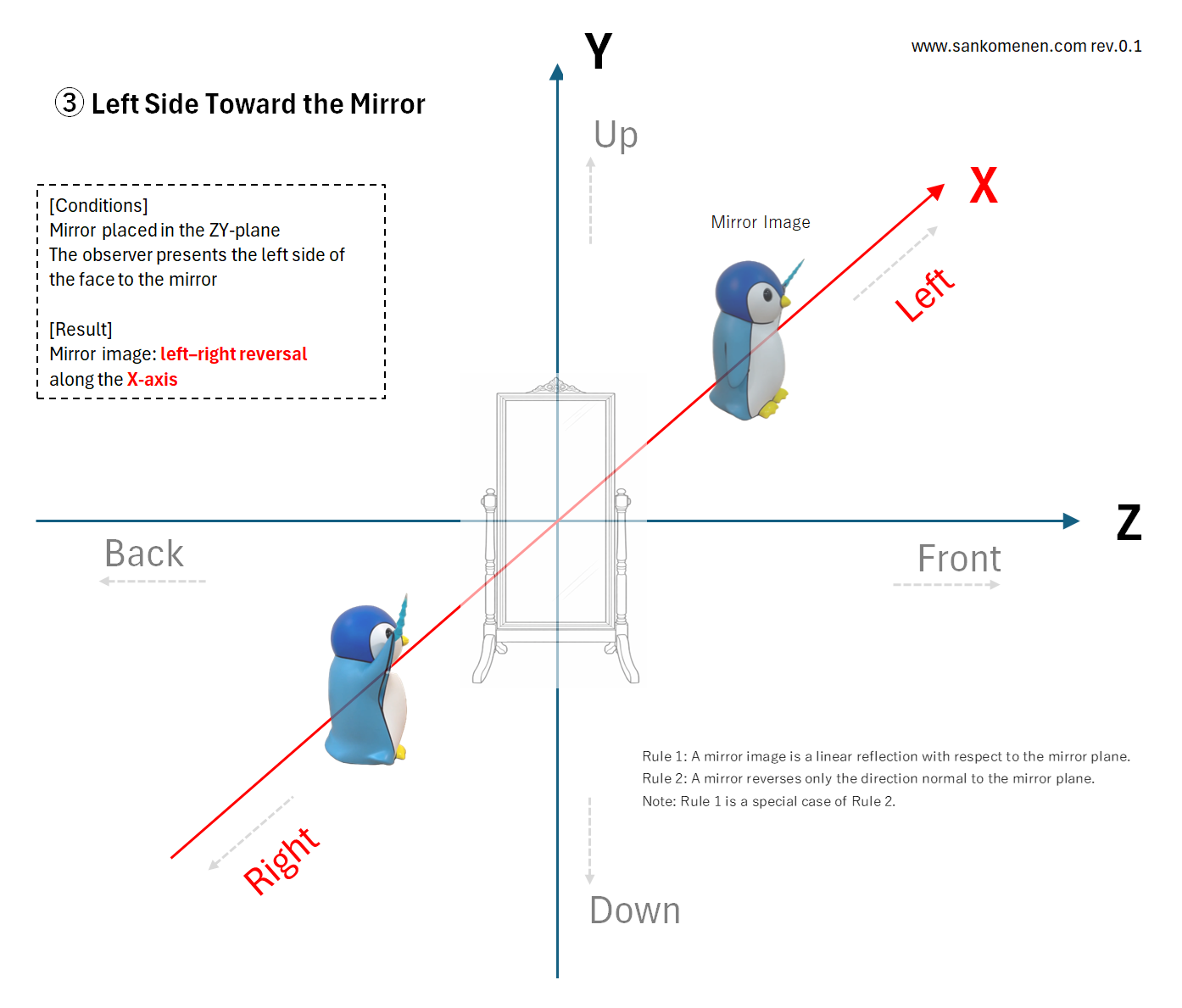

- 6.3 Configuration ③: Side-Profile Orientation (Observer’s Left Side Toward the Mirror)

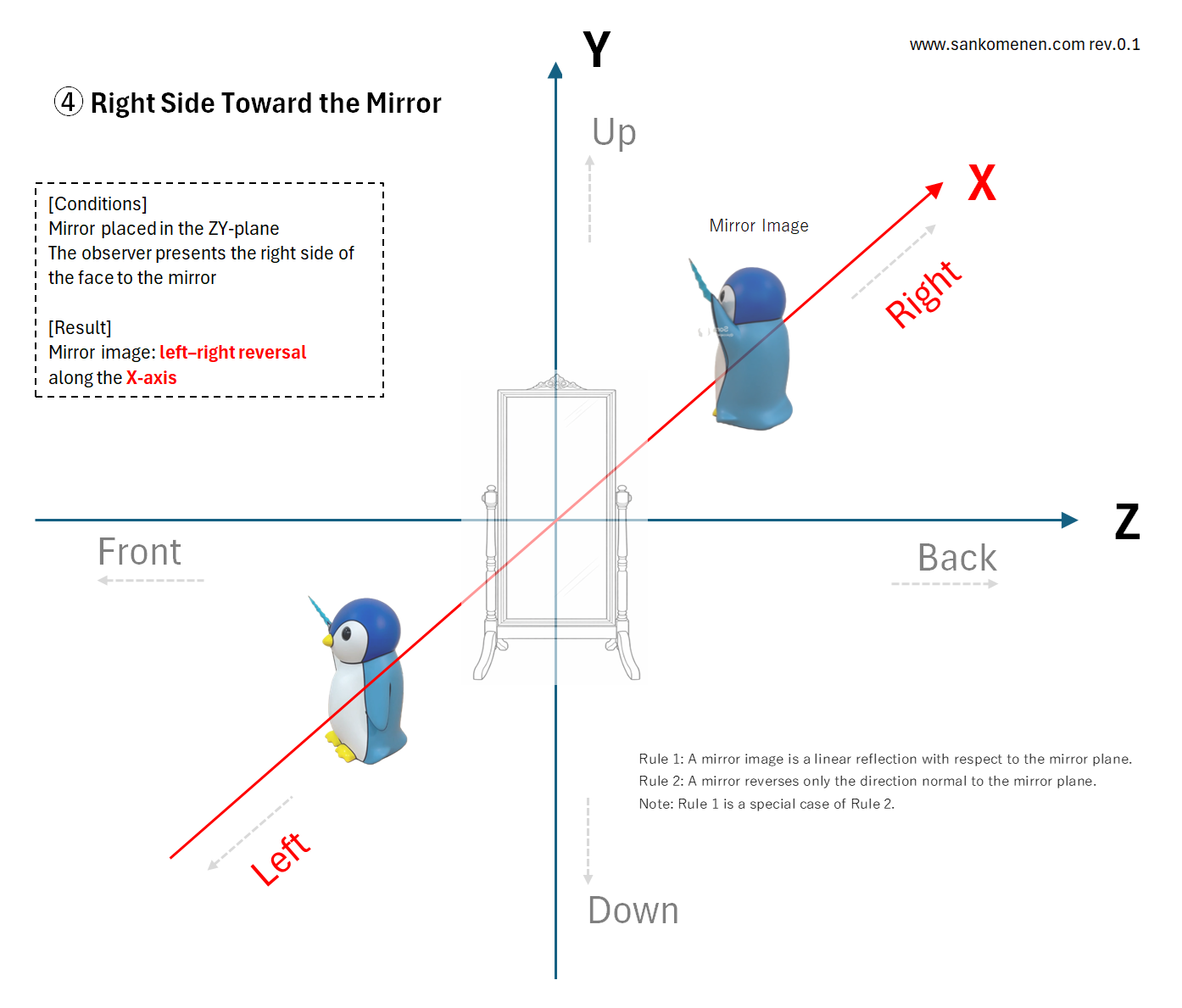

- 6.4 Configuration ④: Side-Profile Orientation (Observer’s Right Side Toward the Mirror)

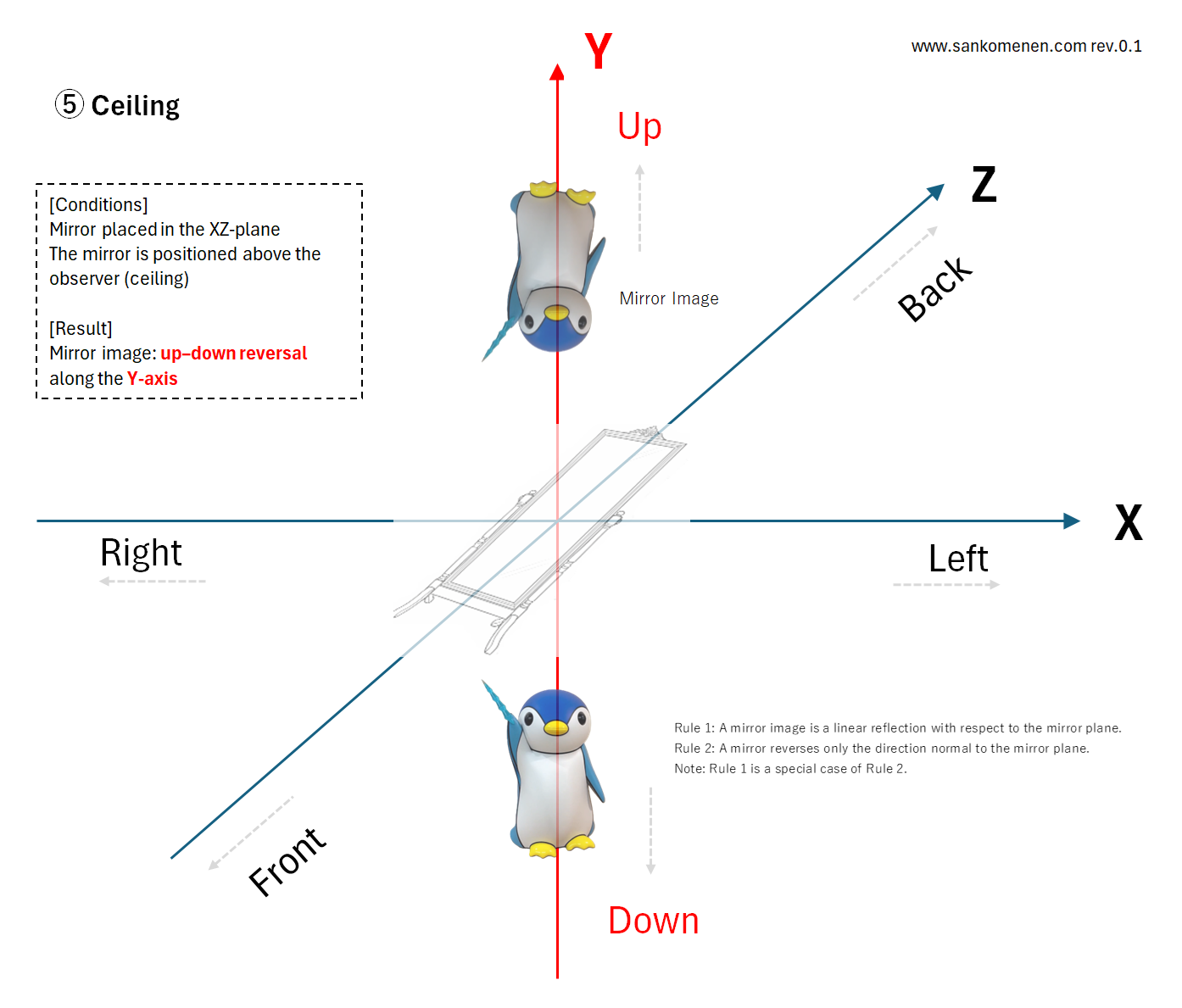

- 6.5 Configuration ⑤: Mirror Placed Above the Observer (Ceiling)

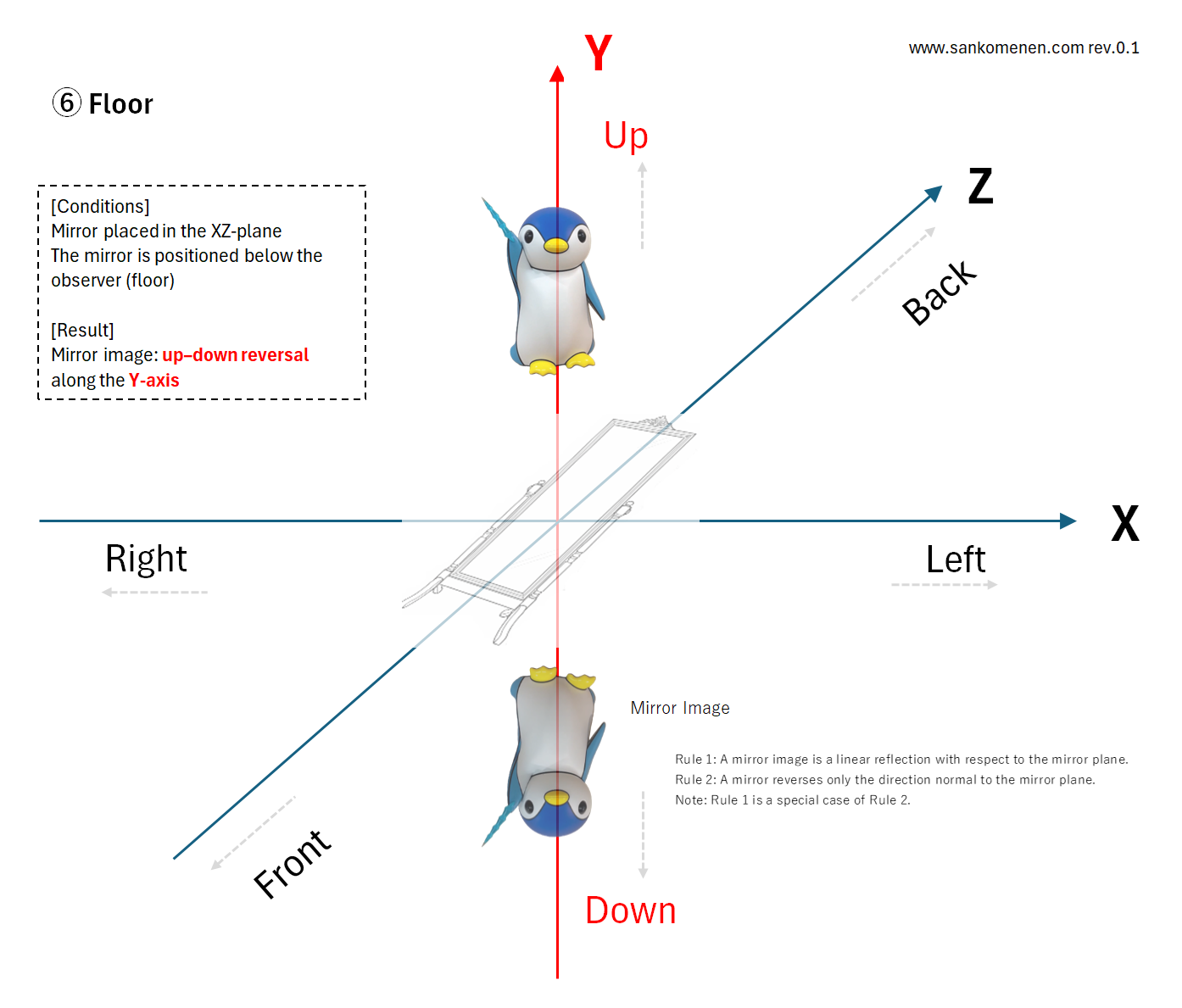

- 6.6 Configuration ⑥: Mirror Placed Below the Observer (Floor)

- 7 Conclusion: Mirror images reverse front–back, left–right, and up–down, depending on the configuration

— Left–right, front–back, and up–down reversals are determined by observer–mirror configuration

Note: This article assumes familiarity with basic spatial reasoning, coordinate systems, and logical conditions, and is intended for readers with a STEM background.

A mirror does not reverse left and right in general; left–right reversal occurs only in a side-profile configuration.

Chapter 1. The Standard View of Mirror Reversal

A widely accepted explanation of mirror behavior states that mirrors do not reverse left and right, but instead reverse front and back.

This explanation is commonly presented in terms of spatial orientation: when a person faces a mirror, the reflection can be described as an inversion along the axis perpendicular to the mirror plane. From this viewpoint, the mirror swaps what is in front of the observer with what is behind, while the left–right and up–down axes remain unchanged.

In the familiar frontal setup, this description appears to match everyday observation. When an observer raises their right hand while facing a mirror, the reflected figure also appears to raise a hand on the right side of the image. Likewise, the left side of the observer corresponds to the left side of the reflection.

For this reason, the front–back reversal explanation is often treated as a complete account of mirror behavior, and is frequently used to resolve the apparent paradox of left–right reversal. Importantly, this explanation is correct within its intended context and provides an accurate description of the observed behavior.

However, as will be examined in the following chapters, this standard view implicitly relies on a specific spatial arrangement between the observer and the mirror. Understanding the scope of this assumption is essential before extending the explanation to other configurations.

Chapter 2. Where the Standard Explanation Works—and Where It Breaks

The standard explanation of mirror reversal is not wrong. However, the widespread confusion surrounding mirror behavior does not arise from the explanation itself, but from two separate issues that are often left implicit.

The first issue concerns observer–mirror configuration. The front–back reversal description applies only to a specific spatial arrangement: the case in which the observer directly faces the mirror. In this configuration, the mirror plane is perpendicular to the observer’s front–back direction, and describing the reflection as a front–back reversal is both accurate and sufficient. The explanation, however, does not claim—and does not imply—that the same description remains valid when the observer’s orientation changes.

Confusion emerges when this configuration-dependent description is treated as universal. When the observer is no longer facing the mirror directly, the spatial relationship between the observer and the mirror plane changes. Extending the frontal explanation to these different configurations is therefore not valid, since the explanation was derived only for the frontal configuration.

The second issue lies in the use of language. In everyday discourse, reversal (inversion) is often used loosely to describe apparent changes caused by body rotation. In a mathematical description of mirror images, reversal (inversion) refers to a mirror mapping: a reflection with respect to the mirror plane, in which one coordinate component changes sign (from positive to negative, or vice versa).

These meanings are fundamentally different. An apparent change in left, right, front, or back caused by body rotation is not the same operation as a mirror mapping. In the mirror case, reversal (inversion) is realized as reflection across the mirror plane. Conflating these distinct meanings obscures the actual mechanism at work in mirror images.

The standard explanation does not clearly distinguish between observer–mirror configuration and the difference between everyday and technical meanings of reversal (inversion). As a result, the range over which the explanation remains valid is easily misunderstood. Recognizing the role of configuration and fixing the meaning of reversal (inversion) in its mathematical sense are necessary steps toward a precise and systematic analysis of mirror behavior.

Chapter 3. The Aim and Perspective of This Article

The purpose of this article is not to restate the standard explanation of mirror reversal using different wording. Nor is it to propose a new interpretation of familiar observations. The physical principles governing mirror reflection are already well established and are not in dispute.

Instead, this article adopts a different analytical perspective. Specifically, it treats mirror reversal as a problem determined by the relative configuration between the observer and the mirror, rather than as an intrinsic property of the mirror itself or a consequence of human perception.

By focusing on observer–mirror configuration, the discussion shifts from general statements about mirrors to a structured analysis of spatial relationships. This approach makes it possible to distinguish clearly between cases that are often conflated, and to evaluate each configuration on its own geometric terms.

This perspective also differs from many existing explanations in one important respect: it aims to be exhaustive. Rather than relying on a single representative setup, the analysis considers all fundamentally distinct configurations that can arise between an observer and a mirror.

The goal of this reorganization is precision. By making the governing conditions explicit, the article seeks to identify exactly when left–right reversal occurs, and when it does not, without appealing to intuition or informal reasoning.

Chapter 4. The Key Insight: Observer–Mirror Configuration

The central insight of this article is straightforward: whether left–right reversal occurs is determined by the configuration between the observer and the mirror. It is not determined by the mirror alone.

A mirror does not inherently encode notions such as left, right, front, or back. From a geometric standpoint, a mirror performs a single operation: it reflects points across a plane. Which directional distinctions appear to be reversed depends entirely on how that plane is oriented relative to the observer.

Once the observer–mirror relationship is taken as the primary variable, the problem becomes well defined. Questions about perception, intuition, or everyday interpretation are no longer required. The outcome in each case follows directly from the spatial arrangement.

This shift in perspective has an important consequence. Instead of asking what mirrors do in general, we can ask a more precise question: What happens for each distinct observer–mirror configuration?

When framed this way, mirror reversal is no longer a single phenomenon with a single explanation. It becomes a set of configuration-dependent outcomes, each governed by the same geometric rules but yielding different observable results. This configuration-based approach provides a unified framework for analyzing mirror behavior. It makes it possible to identify, without ambiguity, the specific conditions under which left–right reversal occurs, as well as those underwhich it does not.

Chapter 5. Why Six Configurations Are Sufficient

At first glance, the number of possible relationships between an observer and a mirror may appear unlimited. After all, both the observer’s posture and the mirror’s placement can vary continuously in everyday situations. However, for the purpose of analyzing mirror reversal, these apparent degrees of freedom are not all relevant.

The key point is that mirror reflection is governed not by continuous variations in angle, but by the orientation of the mirror plane relative to the observer’s body-centered coordinate system. Small changes in position or rotation do not alter which coordinate axis is inverted by the reflection, and therefore do not produce fundamentally different outcomes.

When this observation is taken into account, the problem becomes discrete rather than continuous. From the observer’s perspective, the mirror plane can be oriented in only three fundamentally distinct ways:

perpendicular to the front–back axis,

perpendicular to the left–right axis, or

perpendicular to the up–down axis.

For each of these orientations, there are two possible directions along the corresponding axis, differing only by sign. These sign differences represent distinct configurations, but they do not introduce new types of geometric behavior beyond those already captured by the axis itself. As a result, the complete set of fundamentally distinct observer–mirror configurations consists of:

3 mirror-plane orientations × 2 directional alignments = 6 configurations.

This set is exhaustive. Any real-world arrangement between an observer and a mirror can be mapped onto one of these six cases without loss of generality. No additional configurations exist that would produce a different pattern of axis reversal.

The classification is also non-redundant. Each configuration corresponds to a unique geometric relationship between the observer and the mirror plane, characterized by a specific axis of inversion. No two configurations yield the same transformation. With this finite and complete set established, the analysis can proceed systematically. Each configuration can now be examined individually, allowing left–right reversal to be identified precisely as a configuration-dependent outcome rather than as a general property of mirrors.

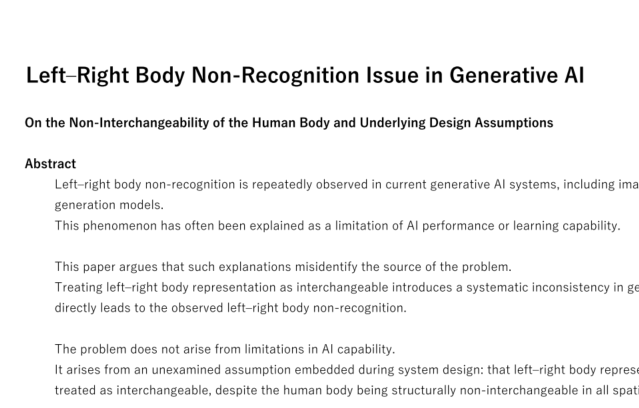

The six fundamentally distinct observer–mirror configurations are summarized in Table 1.

This table represents a complete and non-redundant classification based on mirror-plane orientation and axis inversion.

Chapter 6. The Six Fundamental Configurations Explained

With the complete set of observer–mirror configurations established, we now examine each case individually. Each configuration is analyzed under the same geometric criteria—the orientation of the mirror plane and the direction of inversion—so that all results follow directly from the observer–mirror relationship.

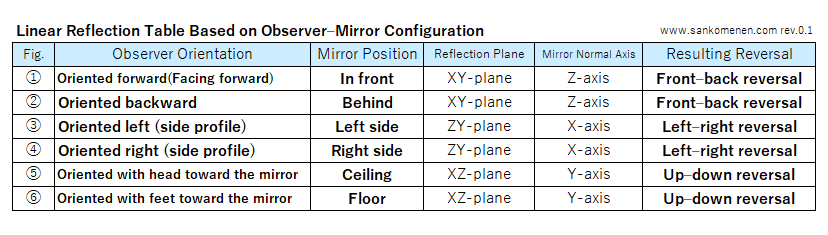

Configuration ①: Frontal Orientation (Observer Facing the Mirror)

In this configuration, the observer faces the mirror directly. The mirror plane coincides with the XY plane, and its normal is aligned with the Z-axis.

Under reflection across the mirror plane, the Z-coordinate changes sign, while the X- and Y-coordinates are preserved. Geometrically, this corresponds to an inversion along the axis perpendicular to the mirror surface.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits a front–back reversal. Left–right and up–down orientations remain unchanged: the left side of the observer corresponds to the left side of the reflected image, and the right side corresponds to the right.

This configuration matches the spatial arrangement implicitly assumed in the standard explanation of mirror reversal. Within this specific setup, describing mirror behavior as a front–back inversion is both accurate and sufficient.

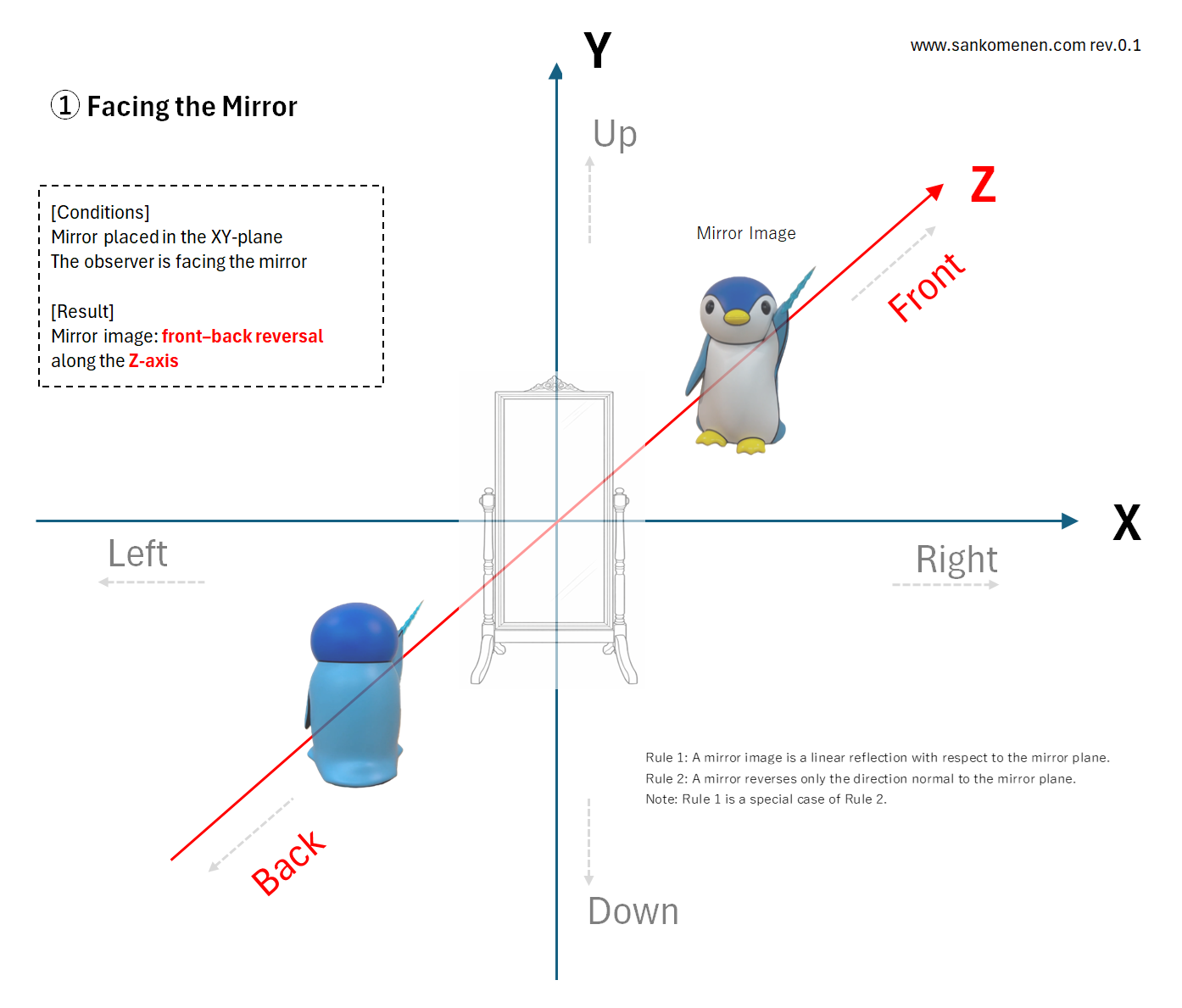

Configuration ②: Back Orientation (Observer's Back Toward the Mirror)

In this configuration, the observer's back is toward the mirror. The mirror plane coincides with the XY plane, and its normal is aligned along the Z-axis.

Under reflection across the mirror plane, the Z-coordinate changes sign, while the X- and Y-coordinates are preserved. The observer’s facing direction differs from that in Configuration ①, but this does not affect the axis of reflection.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits a front–back reversal, while left–right and up–down orientations remain unchanged.

Configuration ③: Side-Profile Orientation (Observer’s Left Side Toward the Mirror)

In this configuration, the observer’s left side is toward the mirror. The mirror plane coincides with the YZ plane, and its normal is aligned with the X-axis.

Under reflection across the mirror plane, the X-coordinate changes sign, while the Y- and Z-coordinates are preserved. This geometric transformation corresponds to an inversion along the axis perpendicular to the mirror plane.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits a left–right reversal. The observer’s left and right sides are interchanged in the reflected image, while front–back and up–down orientations remain unchanged.

This outcome follows directly from the observer–mirror configuration. The left–right reversal observed here arises solely because the mirror plane is perpendicular to the observer’s left–right axis and does not require any additional assumptions.

Configuration ④: Side-Profile Orientation (Observer’s Right Side Toward the Mirror)

In this configuration, the observer’s right side is toward the mirror. The mirror plane coincides with the YZ plane, and its normal is aligned with the X-axis.

Reflection across the mirror plane inverts the X-coordinate while preserving the Y- and Z-coordinates. The geometric transformation is therefore identical to that in Configuration ③.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits a left–right reversal. The observer’s left and right sides are interchanged in the reflected image, while front–back and up–down orientations are preserved.

This outcome follows directly from the observer–mirror configuration. The appearance of left–right reversal here is not exceptional, nor does it require any additional assumptions. It arises solely because the mirror plane is perpendicular to the observer’s left–right axis.

Configuration ⑤: Mirror Placed Above the Observer (Ceiling)

In this configuration, the mirror is placed above the observer, at the ceiling. The mirror plane coincides with the XZ plane, and its normal is aligned with the Y-axis.

Reflection across the mirror plane inverts the Y-coordinate while preserving the X- and Z-coordinates. Geometrically, this corresponds to an inversion along the axis perpendicular to the mirror surface.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits an up–down reversal. The observer’s up and down orientations are interchanged in the reflected image, while left–right and front–back orientations remain unchanged.

This outcome again follows directly from the observer–mirror configuration.

Configuration ⑥: Mirror Placed Below the Observer (Floor)

In this configuration, the mirror is placed below the observer, beneath the feet (floor). The mirror plane coincides with the XZ plane, and its normal is aligned with the Y-axis.

Reflection across the mirror plane inverts the Y-coordinate while preserving the X- and Z-coordinates. The geometric transformation is therefore identical to that in Configuration ⑤.

As a result, the reflected image exhibits an up–down reversal. The observer’s up and down orientations are interchanged in the reflected image, while left–right and front–back orientations remain unchanged.

The geometric transformation is therefore identical to that in Configuration ⑤.

Conclusion: Mirror images reverse front–back, left–right, and up–down, depending on the configuration

The analysis of all six observer–mirror configurations leads to a clear and unambiguous conclusion.

A mirror does not reverse left and right in general.

Left–right reversal occurs if and only if the mirror plane is perpendicular to the observer’s left–right axis, with front–back and up–down orientations preserved—this occurs only in side-profile configurations.

In frontal configurations, the mirror plane is perpendicular to the front–back axis, resulting in front–back reversal while preserving left–right and up–down orientations.

In vertical configurations, the mirror plane is perpendicular to the up–down axis, resulting in up–down reversal while preserving left–right and front–back orientations.

These outcomes follow directly from the same geometric rule in every case: a mirror reverses only the direction normal to its surface. The apparent diversity of mirror behavior arises solely from differences in observer–mirror configuration, not from any special property of mirrors or from perceptual effects.

By classifying all fundamentally distinct configurations and examining each under identical rules, left–right reversal is revealed to be neither mysterious nor paradoxical. It is simply a configuration-dependent consequence of planar reflection—and it occurs only in the side-profile case.

Optional: Governing Rules of Mirror Images

Using only these two rules—one a necessary-and-sufficient condition and the other a necessary condition—we can clearly explain all three outcomes: left–right, up–down, and front–back reversal.

Rule 1: A mirror image is a linear reflection with respect to the mirror plane. (The necessary and sufficient condition for a mirror image.)

Rule 2: A mirror reverses only the direction normal to the mirror plane. (This is one necessary condition implied by Rule 1.)

Note: Rule 1 ⊂ Rule 2. (The set of cases satisfying Rule 1 is a subset of those satisfying Rule 2.)